Αθανάσιος, No Mere Mortal

Mary Kalamaras

Essay

As a Greek girl growing up in New Jersey, I was routinely exposed to the words and deeds of many ancient and modern legendary Greeks: Plato, classic philosopher; Leonidas, defender of Sparta; Onassis, shipping magnate; Zorba, passionate yet provocative peasant, and so on. I learned about these men while working at my father’s diner, overhearing reverent discussions about them during games of backgammon played by our Greek regulars—a clique of mustachioed men who hogged my tables while fingering worry beads and drawing lazily on their Kools.

Despite their rampant chauvinism and cheap tips, I tolerated these mostly older men, who, no matter how often they retold the heroic epics, never seemed to draw any inspiration into their own lives. Instead, they believed they were wired for wisdom and, as such, expected to be shown the proper deference given their superior Hellenic lineage. Simply put, they were the “most Greek” of any Greek men I knew.

“Eh, Maria, bring us more coffee,” Panayiotis would call out, eyeing me carefully as he picked at his tooth with a long pinky nail. Ever-surrounded by younger, dark-haired, gold-chain-wearing sycophants, Panayiotis, or Pete to “stupid Americans,” was a μάγκας, a tough guy who had a weakness for blonde mistresses—American, of course—and would sooner punch you to end a political disagreement than to engage in rational discourse.

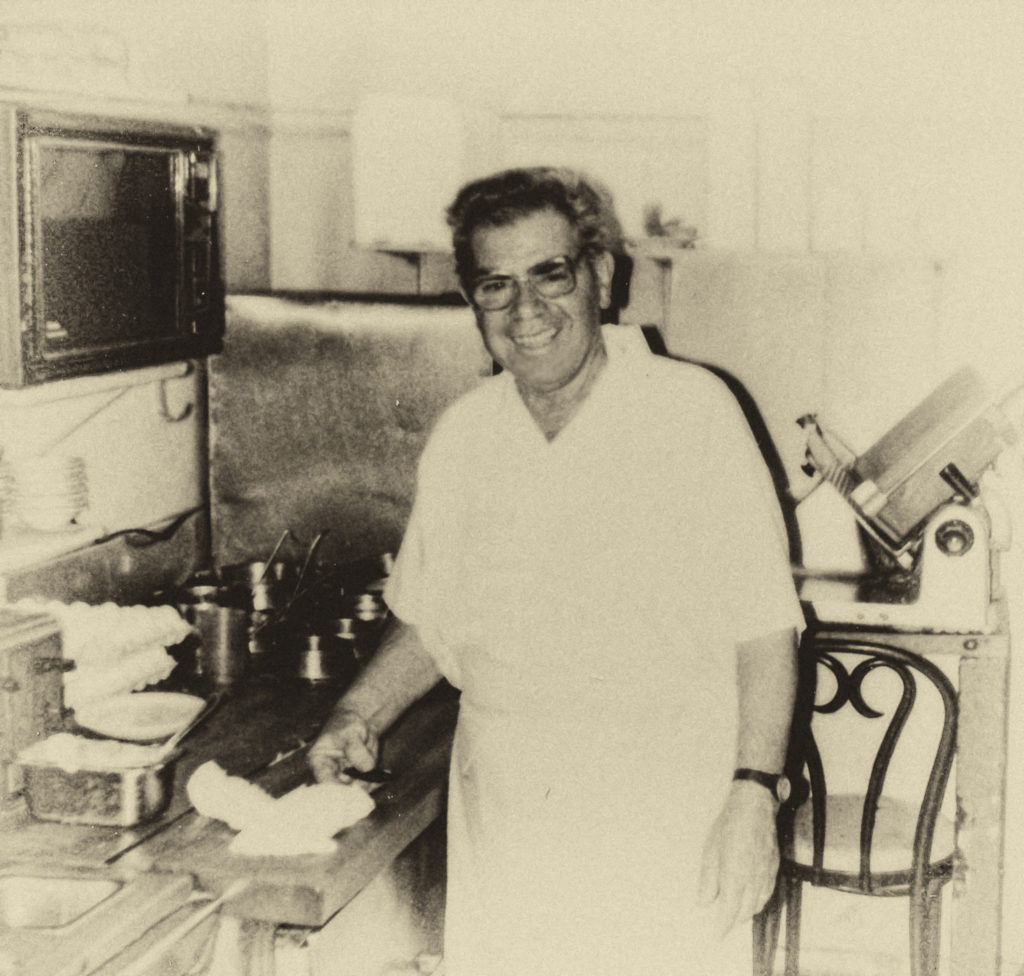

Then there was my father, Αθανάσιος, or Tom to the rest of the customers he adored and who adored him back. He was in many ways the “least Greek” of any Greek men I knew. He suffered fools like Pete for the modest revenue they brought the diner, but he had no time to philosophize—not when working eighteen-hour days. He wasn’t a natural businessman, but he was a mogul in his generosity and concern for the people around him, whether it was his pizzeria-owner pal up the street who sometimes needed a few bucks to make the store rent or a disheveled wandering soul who would be given a seat at the counter and a free hamburger and coffee.

My father never quite fit in with his peers, the restless men, who after having defended their compatriots from Mussolini and the Axis, had emigrated along with him from tiny villages in the Peloponnese region of southern Greece. They quickly settled in the States to become housepainters, factory workers, car mechanics, and, as in the case of Tom and his brother, Bill—a masterful cook who had earned his culinary chops in the army—diner owners. Across the decades, the number of our Greek patrons grew, as did the familiarity with which some of the men would needle my father, the one Greek who wouldn’t needle back. They’d pester my Uncle Bill about how his brother wasn’t any fun—always working and never going out to grab an ouzo and perhaps more.

To Tom, that lifestyle was ανάθεμα, vehemently disliked. He opted for loyalty and industry. He was a loving soul who never uttered a harsh word at me, my mother, or my two brothers. And to prove himself worthy of his family, he worked and worked and then he worked some more—cooking, cleaning, serving, delivering.

Still, he was considered a softie by some, in particular by a Greek from Toronto named Gus, who was often sarcastic in a saccharine sort of way and underhandedly disrespectful. My father always ignored the asinine jokes Gus told at his expense about his weight or intellect. That is, until one Saturday morning at the height of the breakfast rush, when Gus made the ill-fated executive decision to push my father’s patience too far by poking at him from a different angle.

At first, I hadn’t noticed Gus standing at the end of a long line of customers paying their tabs. I was in the zone, rapidly dispatching each person with a steady rhythm of offering a greeting, spiking the green check on a spindle, counting out change, and retaining in my head several iterations of breakfast orders that I had yet to shout out to my uncle in the kitchen. When Gus’s turn came, instead of handing over his money along with his daily lecherous wink, he and his migraine-inducing Halston Z-14 cologne lingered off to one side.

“Is there something wrong with you?” I remember asking as he leisurely assessed my waitress uniform top.

“No, you are a beautiful woman, Maria. Why no boyfriend for you?”

Back then I wasn’t great at handling this sort of thing, so I ignored him, took out my checkbook, and began adding up totals until he finally stepped up to the register. In a clingy polyester shirt that resembled a Jackson Pollack painting tracked through mud and garnished by a Parthenon medallion necklace, he was a Dollar Store Dionysus: standing tall with an air of impending conquest and not a small hangover from the previous night’s escapades. Not caring that he was within earshot of my father who was behind me, wrapping up pork roll-and-egg sandwiches for a waiting family, Gus decided to proposition me just as I tried to hand him his change. It wasn’t the first time, but it was the pushiest yet.

“Κούκλα, my wife is in Greece,” he purred, aggressively clasping his rough hand over mine as I tried to release bills and coins into his. “Ελλα μαζι μου απόψε. Come out with me tonight.” A dark glint in his bloodshot eyes, a roll of the toothpick in his grinning mouth—it was brazen, even for him.

Before I could respond or break free from his hold, movement flashed behind me. Then appeared a large sandwich knife nicknamed Θηρίο, or “the Beast,” for its ability to send people to the emergency room. Wielding it was a man I had never seen before, eyes alit with a bull’s anger and whose reflexes put Hermes to shame.

Then came the roar: “Get the hell out of here now, ορνιό!” as the knife was pressed against Gus’s exposed neck.

Gus’s eyes widened immediately in genuine shock at having been called a vulture and then filled with indignation at the public humiliation. At the intersection of these emotions came the only glimpse of honesty I would ever witness in Gus. He was psychologically knocked over, sent mentally reeling. But as quickly as he lost his cool, so did he try to regain it: first with a smirk, then a raise of the shoulders, a tilt of the head, and a wordless retreat out the front door.

The entire time, a diner full of customers, including the local judge and his posse of lawyers, had been transfixed by the action, allowing it to unfold but ready to intervene on behalf of their beloved Tom. Once their collective breath was released and they began calling out their support for my father and comments of good riddance over Gus, I caught something fresh reflected in their faces, something beyond affection. It was awe. Like me, they had for a moment witnessed Theseus come to life, the god warrior who had struck down the Minotaur.

Throughout the many years that followed—and especially when my loving Baba waged his warrior battle with the cancer that would eventually vanquish him—I would think back to that Saturday morning, grateful for the man who fought for my honor and protection and proud that the Spartan blood that ran through his veins also ran through mine.

Mary Kalamaras is a freelance editor living in the Boston area with her scientist-husband, John Quackenbush, and teenage son, Adam. She enjoys playing piano and drums and is an avid photographer. She is also on a never-ending mythic quest to find a cup of coffee that rivals what her father served at the Amboy Luncheonette.

Image Credit: Mary Kalamaras