New Life for Old Things

Patricia Crisafulli

Original Short Fiction

Old battles, she told herself, returning to the silverware, deeply and badly tarnished. Once it had been stored lovingly in a velvet-lined wooden box in a cabinet in her mother’s dining room. That was thirty years ago, before her mother had gone into assisted living then a nursing home and then passed away. Her brother, her only sibling, had no interest in any of it, so Marni had taken her mother’s things into her home—to keep, to preserve, not just material possessions, but also the memories of her mother.

Now, combined with four decades of life in this house, it was all too much. She needed to lighten the load.

Reduce, reuse, recycle…. What applied to their glass jars and plastic containers, they needed to adapt to bigger and even more valuable things. She paused and added another r-word to her litany. Release.

Rummaging in the laundry room cupboards, Marni found an unopened package of tarnish removal cloths. The label warned of fumes, so she cracked the kitchen window and put on gloves. Tarnish dislodged, dissolved, and disappeared in a way that became hypnotic, like some kind of fun-with-science project—the baking soda and vinegar volcano she had long ago entertained her nieces and nephews with—although, thankfully, the tarnish removal trick didn’t make a bigger mess. Filling the sink with hot, soapy water, she slipped in the now-shiny silverware and watched it shimmer, like a school of smelt in a spring run.

Upstairs in the linen closet, Marni dug until she found a hinged box. Inside were stacks of receipts from trips they had taken more than ten years ago. To the shredder, Marni pronounced, as she heaved the lot of it into a paper grocery bag and carried the box downstairs. By the time she had hand dried the complete set of silverware and put it into the boxed lined with several tea towels, she had a plan.

Her neighbor, Susan, answered Marni’s knock, surprised to see her—they were friendly, but not friends. Marni started in with the little script she had prepared in her head.

“First of all, I’m not crazy and I’m not dying.” Marni smiled with assurance. “I’m cleaning and I found this—it was my mother’s. Sterling, set of 12. I thought Stacy would like it, she’s getting married, right?”

“Tracy,” Susan corrected.

“Of course.” Marni raised the lid and the silver shone. “It should be used and enjoyed, not just stashed in a drawer.”

Susan asked Marni in and called for Tracy who, as it turned out, was visiting for the day. Marni repeated the story, including the not crazy and not dying part, and offered the girl the silver. “Don’t take it if you hate it. Be honest.”

Tracy picked up a seafood fork with its trident prongs. “This is so cool. I love it.”

“She’s very into vintage,” Susan laughed.

Marni really wanted to get back, but came in for a cup of coffee, listening to wedding plans with a Pride and Prejudice theme. Susan handed her a fat envelope. “Wedding invitation. You and Russell have to come.”

Marni promised they would try their best to be there.

Russell was the reluctant one, resisting the suggestion that he part with one of two socket wrench sets and power tools he hadn’t touched in years. Finally, little by little, drawers emptied, and the basement cleared. Goodwill and the Salvation Army picked up furniture and bedframes, although the mattresses had to be junked. Every week, their recycling bin filled to brimming with old papers, cracked glassware, and plaster thingamabobs.

“We moving?” Russell asked more than once, at first joking and later in a tone tinged with fear.

“We have too much, Russ,” Marni said. “It’s time to find a new home for what’s still worth something to somebody. And we don’t have any somebodies to give it to.”

Their wills provided for their favorite charities dedicated to equality in education and environmental conservancy. Not that they were going anywhere, she at sixty-nine and Russ at seventy-four; good health meant they probably had ten to twenty years left. But their stuff shouldn’t be a burden on distant relatives—Marni’s nieces and nephews or Russell’s cousins’ children. Having seen Tracy’s reaction to the silver and china, Marni knew they needed to pass on the good stuff to people who would find joy in it.

They needed to have a party.

They sent out electronic invitations, a first for Marni who delighted in how easy it was to change the theme, color, and font with a click of a mouse. They called the evening “To Treasured Friends” and invited former colleagues from the university, former students they stayed in touch with, friends, and a few neighbors. Whenever one or the other thought of another name to add, out went an invitation. By the appointed Saturday, the RSVP list numbered 46. The caterers and servers were hired, the menu planned, the backyard strung with white lights. Then Marni prepared the gifts.

Her first thought was a grab bag, leaving to chance who got what. But to do it right, there needed to be notes to explain context and intention. She picked up a strand of jet beads separated by little silver knobs and thought of, Iris, the executive assistant in the biology department who, Marni remembered, liked such things. These beads belonged to my grandmother. I can remember her wearing them every Sunday to church. I know it would please her if someone wore them again. I thought of you.

Russell had a very fine set of drafting tools, compasses and styluses, more antique than useful, and wrote a note in his strong block letters to a former student. Jonathan – I actually used these in my early days, long before anyone thought of CAD programs. Maybe you’d like to have them…

They started with their best possessions, things that had once given them joy, but which they rarely saw or thought about anymore. They supported each other in parting with things that were hard to let go of at first, but by the morning of the party forty-six wrapped presents, each personalized with a note, were arranged on the sideboard.

Marni wore a flowing dress found in the back of her closet and put her hair up, instead of in the usual clip at the back of her head, along with pair of garnet earrings Russell had bought for her on their honeymoon to Italy forty years ago. As dear as that memory was, she had temporarily forgotten about the earrings until unearthing them in what Marni now thought of as the great treasure hunt.

People came, bearing bottles of good wine and flowers that filled the vases that Marni had carted out of the basement for just such a contingency. Russ had turned the radio to the classical music station, but when former students brought guitars and a small sound system, they had live music in the backyard. Carlos from the foreign language department performed a flamenco with his wife, who was the far better dancer. When Carlos urged others to join in, Susan, their neighbor, was the first to jump to her feet, pulling her husband with her. Soon there was a crowd on the brick patio, stomping their heels and clapping their hands. Marni leaned her head on Russ’s shoulder, deeply content at what they’d created.

The first guests left at about eleven, and Marni rushed to the front door with their gifts in hand. “Open them at home. Just something Russ and I want you to have.” She repeated this sendoff dozens of times over the next hour and a half. Some people put up their hands in polite protest; others took the boxes with grateful excitement.

As the servers made their last check of the kitchen, Marni looked in drawers and cupboards for something to give them, along with a cash tip. They left with decorative aprons, never worn; salad serving sets, some carved from olive wood, others made from water buffalo horn and inlaid with shell; and two lacquer trays, one decorated with wine bottle labels and the other scenes from Paris cafes. The bartender who had kept the wine flowing all evening was more than happy to take the vegetable steamer, never used and still in the box.

The next morning, phone calls, emails, and texts thanked them for the gifts. “Are you sure you want to part with this?” more than a few asked, and needed to be assured that, yes, they did. Iris texted a selfie, wearing the jet bead necklace. The former student emailed a short video of himself drawing with the old drafting tools. A former colleague who taught archeology sent a photo of the carved gourd from Peru on a shelf with mementoes from his own travels.

At about three in the afternoon, as Russ napped on the sofa and Marni read in the armchair with her feet up on an ottoman, the doorbell rang. Russ stirred before Marni could gather the willpower to shift out of her comfort.

Jake, one of Russ’s former students, came into the living room with a dark-haired man who had attended the party with him. Eric! Marni remembered his name and greeted them both.

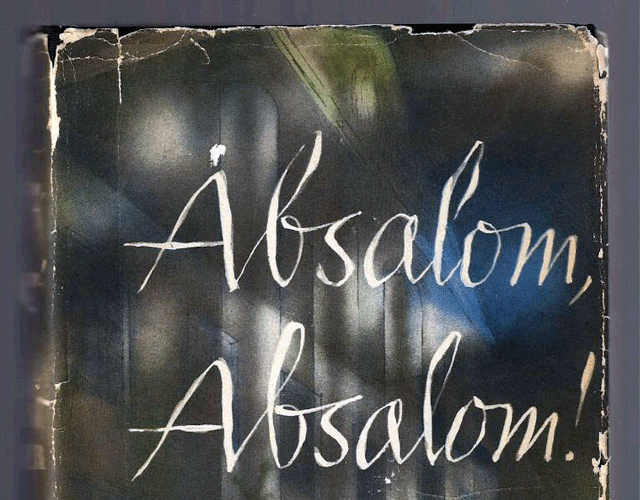

Jake held Falkner’s Absalom, Absalom! in his hand as he sat, facing Marni and Russ. “This isn’t just a first edition from some subsequent print run. It’s from the first edition. And it’s signed.”

“It’s worth somewhere between nine and ten thousand dollars,” Eric added. “We can’t accept this.”

“Why not?” Russ protested. “Jake, you were the only student I knew who majored in engineering and English. I figured you’d probably have the patience and inclination to plow through Falkner. I confess, I never could get beyond a few pages. Too dense for me.”

“It’s too valuable. You should give it to someone in your family or sell it to a collector,” Jake protested.

Eric leaned forward, elbows on his knees. “I’m a social worker, and I do a lot in geriatrics.”

The word stung Marni, though she was fully aware of her age.

“When people give away their possessions,” Eric continued.

“Stop!” Marni practically shouted. “We aren’t dying and we’re not killing ourselves, if that’s what you are trying to imply.” Suddenly every bit of joy she’d felt in planning the party, in giving things away, in lightening their load, was replaced by shame and humiliation. They were old fools, foisting their junk on other people.

Russ reached for her hand and held it tightly. “We appreciate the concern, but there’s no worry.”

Jake ran his palm lightly over the book cover. “Can you tell us why you decided to do all this?”

Marni turned her head and looked at a blank spot on the wall where once had hung a mirror she had given to a neighbor, who no doubt was now wondering what in the world to do with it.

“We have too much stuff for two people. Nice things. Things that other people might like,” Russ began. “So, we threw a party and gave it away.”

When Marni turned back toward them, their faces swam in the tears in her eyes. “We just wanted to make other people happy.”

Eric softened his gaze. “I’m sorry. We didn’t mean to upset.”

Marni held up her hand. “I get it. This was a stupid idea.”

Jake sat back. “Wait, what? That was a great party last night. And giving people your treasured things is really kind and generous. The signed Falkner, first edition, just intimidated me. I thought it should go to someone else.”

Russ shook his head. “No, it should go to you. You’ll keep it, treasure it. Or, sell it if you like.”

“No way!” Jake shot back. “This, I will keep forever.”

Marni smiled for the first time since this awful, awkward, and, ultimately, honest conversation began. “Anybody hungry? We have leftovers from the party.”

They sat in the kitchen around a table set with brightly colored stoneware bought on a trip to Arizona years ago. No more paper plates, she told Russ; they needed to use what they owned.

Jake opened the book and read a little Falkner “From a little after two o’clock until almost sundown of the long still hot weary dead September afternoon they sat in what Miss Coldfield still called the office because her father had called it that….” The first sentence went on and on, a winding tributary of words that became a great river of sound and images, made melodious by Jake’s fine reading voice. When he stopped at the bottom of the page, he took a breath, like a swimmer finishing laps.

Marni opened a kitchen drawer, saw the contents clearly spaced and organized, and reached for a serving spoon to put coleslaw on their plates. “Read some more,” she said.

Old words, shut up in a volume for decades, found a new voice.