Lil Divot and the Driving Lesson

By Dr. Jordan Douglas Smith, PhD

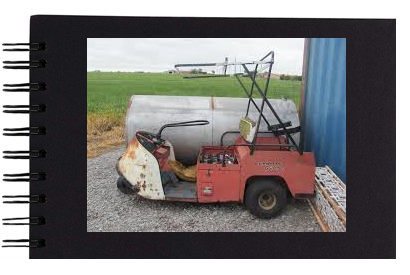

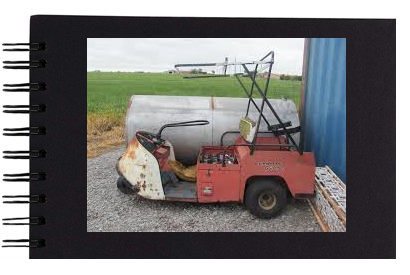

I learned how to drive at Midway Golf Course, the summer after my eighth birthday, on a gas-powered 1956 Cushman Golf cart. These old golf carts don’t have steering wheels, but an obtrusive handlebar that sticks out of the middle of the floorboard, right between the driver and passenger seat. That made it a perfect device for teaching an unruly boy how to drive. Anytime I would get distracted, hesitant, or just plain reckless, Dad grabbed the handlebar and corrected our path.

This golf cart was my father’s pride and joy during the summer of 1990. He worked hard at a factory on the third shift and any additional income he earned always seemed to go towards an “Uh-Oh!” fund my mother had established in an old sauerkraut jar at the back of the bread cabinet. So, when she had given him permission to purchase this old, gently used piece of leisure machinery we were all excited for Dad. If anyone deserved it, Doug Smith did.

Dad wasted no time tuning up his chariot for the course. I recall him speedily finishing up dinner one evening so he could delicately mount the decal christening it “Lil Divot.” The old cart’s burnt orange paint and off-white leather seat seemed less than appealing to my mother. Yet, in my father’s eyes, this ancient artifact pulled his gaze as would a brand-new Ferrari. In less than a week, the cart was ready for an inaugural trek on the local course.

Midway Golf Course sat between Buhler and Inman, Kansas, on 8th Avenue and Arrowhead Road—right on the line separating McPherson and Reno Counties. The terrain was remarkably flat, although Miller Creek snaked through the course providing several obstacles for the amateur golfer and some much-needed shade on a sunny day.

My responsibilities while driving the golf cart meant staying out of the wheatfield to the west, avoiding the barbed wired fence of the north pasture, and not executing sudden turns that would spill Dad out onto the fairway. I failed in these duties at least a half dozen times while learning how to operate that cart. There were a few bridges on the course over Miller Creek, each quite narrow and without side guards. The one off hole number seven was notoriously narrow and had a bump in the middle that could send you rocketing from the seat. In the beginning, Dad took the handlebar as we crossed the bridges—if anything, to guarantee his own safety. He would often remind me, “Jordie, so long as you pay attention, slow down, and be calm, everything will be dandy.”

A theme in my life is throwing caution to the wind when I think I know more than I really do. There are simply certain skills that I have an unhealthy amount of confidence in, making it uniquely difficult for me to embrace humility. Driving Dad’s golf cart became one of those skills that needed a heaping dose of humility.

During the summer between fifth and sixth grades, Dad gave me his blessing to use the golf cart on my own. He would drop me off at the course on Tuesdays with an emergency use-only cell phone, a jug of water, a can of Mountain Dew, and a Ziplock bag of beef jerky, and I would play golf until my hands blistered. During his lunch break, he’d pick me up and drop me off at the pool to practice my cannonball with the boys on my baseball team.

I had this spot on the back of hole number five, slight dogleg left, par four, just under this massive cottonwood tree behind the green. On the west end of the creek bed was a mulberry tree. I would park my cart, climb into the branches, hoard as many berries as my arms could hold, and lay back against the tree to eat my fill. Absolutely no interruptions.

After my mid-morning detour, I would jump back on my trusty steel steed and go right back to perfecting my short game. I knew where all the potholes were so I could avoid rattling the muffler that was barely hanging on—and I also knew this sweet spot off hole six where you could get at least two inches of air if you hit it just right at top speed (which had nothing to do with the muffler barely hanging on, or so I told Dad). Everything was smooth driving, and I was in a constant state of joy.

Then came the storm.

I used to think it was peculiar how storms interrupt the rhythm of nature. In the same way, tragedy often seems to interrupt the steady flow of joy in our spiritual journey. As I’ve become more observant, listen more than I speak, and love without the expectation of receiving, it makes more sense that storms show up during picnics. It’s impossible to grow wheat without rain—or to mature a soul without a little spiritual thunder.

That summer we had record-breaking rainfall—sometimes upwards of six inches in less than two hours. And it didn’t let up. After months with little to no moisture, the water simply rolled off the fields into every creek bed in central Kansas. For a few days the most practice I could get in was putting around the living room into dixie cups. It was torture for a young golfer. Locked indoors, staring at the rain, watching Saved By The Bell reruns.

So, to distract myself and take on some household responsibility, I started training my four-year-old sister on how to be a proper caddy. I figured when the rain let up, I would have someone to bring me my clubs and keep score.

After a little over a week, the storms receded. I was itching to get on the course, so I convinced Dad to drive me out one evening when he got home from work.

As we pulled over the hill approaching Arrowhead Road my heart sank to the floorboards of his truck. Instead of staring out over my small slice of heaven, I was greeted with what appeared to be a new lake straddling the McPherson County line. I could barely make out the roof of the course gazebo sticking out of the flood waters.

We turned around and headed home, while I rattled off dozens of questions: “Will the course be opened when the water dries up? How bad is flooding for the greens? Will we even be able to take the cart out?”

Holding back tears, I kept repeating, “It’ll be fine, everything will dry out, you’ll be back out there in no time.” But inside I was hollow, bitter, and skeptical of every reassurance my father gave me.

When we pulled into our driveway, I jumped out of Dad’s truck and stomped into the house. My mother called out from the living room, “Jordie, what’s the matter?”

Tears in my eyes and a tremble in my voice, I relayed what we’d seen during our scouting mission. My father stood behind me, arms crossed over his chest, while I unleashed my sorrow upon the whole house. My mother’s eyes filled with concern and compassion. In the living room mirror behind her, I could see my father’s face—calm, nearly stoic.

I was confused. Here I was absolutely unhinged, and there was Dad unnerved by the crisis. I turned to him and yelled, “Don’t you get it? The whole summer is ruined!”

With a somber tone and a gentle hand, Dad hugged my shoulder and said, “You need to trust me. Everything is going to work out.”

Frustrated with his response and downright angry at my circumstances, I took off down the hall and slammed my bedroom door. My face planted in my pillow, and my mind fixed solely on all that I had lost, I sobbed.

An hour or so later, my father knocked gently on the door to my room. In his calm, deep voice he asked, “Jordie, want to talk?” But talking was the last thing I wanted to do. I was angry, but also more embarrassed than anything else. Hesitantly, I invited my father in. He sat slowly on the bed and put his hand gently on the top of my head. “You know the water will dry out. So, tell me what’s really bothering you.”

“Dad, this just ruins my plans,” I whined. “There’s only a few weeks left of summer and things were going so well!”

Dad pulled me in close, wrapping his arm around my shoulders. “Son, this is a choice you’re going to have to make a lot in life. The choice is whether you’re going to let a little rain wash out your joy or refresh it. We need the rain, right?”

I sheepishly answered, “Yes.”

“So, I want you to be confident that this is part of the gameplan and find a reason to be grateful.”

When Dad left my room, I was still flustered but now I felt licked too. As I started to think about what I could possibly be grateful for in this disaster, my baby sister burst through the door wearing Dad’s golf cleats. “Jordie, let’s practice putting again!”

I couldn’t help but grin at her tiny frame inside Dad’s size 12 shoes. A smile stretched across her cheeks and Dad’s putter was tucked awkwardly under her arm.

I put on my poker face and commanded, “Caddy, we’ve got a lot of work to do on the greens today. Let’s hop to it!”

As the days passed, my fascination with water tables and proper field drainage became borderline unhealthy. Each day clicked like a timepiece closer to the end of my summer and further away from Lil Divot and the Midway adventures. I sat on the old cart in the garage and closed my eyes, envisioning bouncing around fairway two, winding across the cart path on three, and pulling up to the tee with windblown hair.

Finally, the day came. Dad got out of his truck, a big smile on his face, and instantly I knew. The course was ready.

The next morning as Dad unloaded the cart, he turned to me and said, “Jordie, be careful today. Don’t get too close to the creek where it’s gonna be wet and watch the dew on the bridges. The course has probably changed quite a bit.”

Those words seemed to bounce back and forth in my head: “Be careful. The course has probably changed quite a bit.”

I nodded, then jumped into the trusty Cushman and drove off to tee box one. Passing by the creek, I noticed the water was still about waist high. For late July this was quite a sight. I reminded myself to play the ball short, or I’d be spending a lot of time swimming to find the ball.

Hole one played like I expected. I was a little rusty but so far everything was still in its right place. So, when I pulled up to the first bridge crossing Miller’s Creek on hole two I was surprised to see a “Bridge Closed” sign. Nothing seemed wrong with the bridge. It looked wet, maybe it had shifted a bit from the water, but seemed safe.

To avoid the inconvenience of going around the creek, a detour that would take all of five minutes, I moved the barricade and drove across the bridge. The tires spun like I’d hit a mud slick. A slight shift in the back wheels brought me closer to one side of the bridge. Then the wheels hit the earth on the other side, and I was set to tee off on hole number two!

As I played through the course, the same warning emblazoned on each bridge: “Bridge Closed—Use Detour.” And I moved each barricade and pushed through my course, on my terms.

Then I got to hole number seven and the bridge with the weird bump in the middle.

Approaching that bridge, I noticed how much narrower it seemed than I remembered. I briefly considered leaving the cart and walking this one. But I didn’t. I moved the barricade and hit that bridge going 20 miles per hour in a 500-pound cart on wet wood with no side guards.

There have been six moments in my life when I genuinely thought injury was inevitable. This was moment number two. As I gripped that handlebar for dear life, I saw all my eleven years flash before my eyes while screaming in a high enough pitch for dogs in Harvey County to hear me.

That old steel cart slammed into the creek bank and threw me head over heels up onto the edge of the green on hole seven. I remember doing about three summersaults before landing in a seated position, arms crossed over my chest.

After taking a moment to gather myself, I felt relieved that I had evaded serious injury yet again. But Lil Divot remained half submerged in the muddy waters of Miller Creek.

I stood there on a closed bridge, staring down at Dad’s golf cart and knowing I had made a mess of things. Looking up from the carnage, I locked my eyes on the back of the “Bridge Closed” sign. In bold white letters, surrounded with faded red paint, the word “STOP” boldly professed what I should have done five minutes earlier.

In what can only be described as divine timing, my father pulled into the dirt parking lot.

As Dad walked up the fairway to the seventh green, I kept my gaze on the small letters of the “Lil Divot’ decal affixed to the bumper of the old Cushman. If I didn’t make eye contact, I thought, we could avoid the prelude and just get down to the verdict. Surely, he would be mad, disappointed, maybe even furious. I was absolutely confident that I had ruined his trust in me.

Dad put one hand in his pocket and the other on my shoulder as he looked down into the creek. “This is why we pay attention to signs, bud.” He took a deep breath and added, “Go grab the rope out of my truck and let’s clean this mess up. When we’re done, we’ll play a few holes together.”

As I climbed down the bank to secure the rope to the old Cushman, I choked up a little. I had directly disobeyed my father. Ignoring every sign, I’d been reckless. I did not deserve his grace. Yet here I was, in one piece—and at peace and about to play a round of golf with a man who had every right to leave me standing in my own mess.

Of course, there were consequences for my actions. Later, I had to spit polish that old golf cart till it shined, and eventually I had to pay for a new sparkplug replacing the one damaged in the spill. But where my strength and wisdom were lacking, my father’s more than made up for it.

Dr. Jordon D. Smith, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Communication Studies and speech team coach at Ottawa University in Kansas. He has taught oral interpretation of poetry and prose while coaching numerous national finalists in both categories.