Grenville: Fish and Fowl

Patricia Crisafulli

PART FOUR

“Grenville: Fish and Fowl” revisits the characters in Grenville, N.Y., a tiny Adirondack Mountain town.

T he canoe paddle sliced through the water, angled just right to create propulsion without excessive splash. Karl Arrollson felt the pleasant pull in his shoulders and down his back, the muscles rarely exercised except here among the many lakes and rivers that intersected the Adirondack Mountains. On this early September morning, with fall’s breath in the air, he and Frank Pherson crossed Little Moose Lake. Bass were in season until the end of November, but he was not.

This was his last weekend in Grenville. Already Bambi was packing up their summer house. Tomorrow, they’d head back to Rochester, and that would be it until next Memorial Day. His wife tolerated summers spent in Grenville at the big cottage his parents had built in the 1960s, which had been remodeled and expanded several times since then. It was fine when their friends came for a long weekend; Bambi was happiest as the hostess: pinot grigio and baked brie, Cornish hens on the grill. In return for the better part of the summer spent in Grenville—with many trips back and forth to Rochester where he was still a partner in a law firm, though semi-retired—Karl reciprocated with a week in Palm Springs right after Christmas and a jaunt to Europe in the early spring before the crowds of tourists.

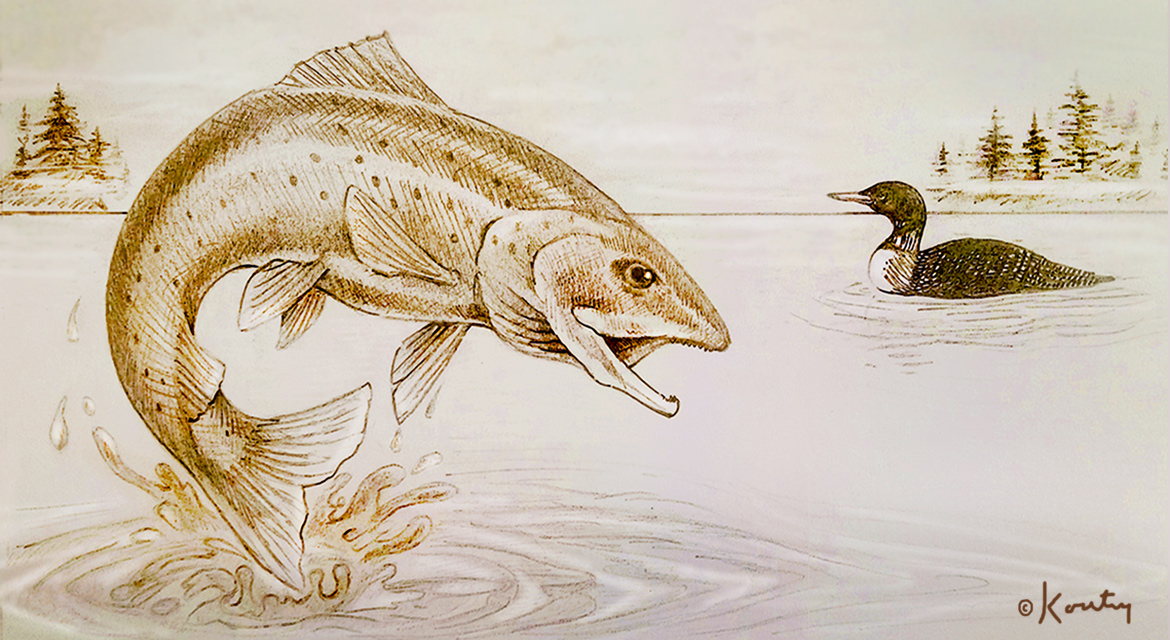

The lake’s surface erupted. “You see that one?” Frank asked.

Karl saw only ripples receding. “What was it?”

“Trout—one of them rainbows, I think, from the way the sun hit it.”

Karl wished he’d seen it, then as if on demand another fish leapt into the air.

“They’re biting, that’s for sure.” Frank resumed paddling and maneuvered them into a cove where overhanging trees shadowed the water. “Caught a good-sized one here a week ago. Large-mouth bass—had him for dinner, too.” Frank grinned. “We’ll get you some today. I’ll clean and filet ‘em for you. Stick ‘em in the freezer overnight. You take them home like that, and you won’t believe how good they taste.”

From across the water, Karl heard a low, mournful wail. He followed the sound to the dark silhouette of a loon bobbing on the surface of the lake. “I thought you could only hear them at night.”

“We must have disturbed him,” Frank said. “Just wait.” Thirty seconds later, another loon answered. “That’s his mate saying all is well.”

Karl cast his line; the hook hit water with a satisfying plop.

Frank held his fishing rod just tight enough to feel any action on the line. If he could make a full-time business of being a fishing guide, he’d never be at the motel. But Karl was his only customer. Fishermen who came to Pine Breezes wanted directions and tips, but they went out on their own.

He tightened his grip, feeling a nibble, but no bites as yet.

They never discussed the incidents earlier in the summer, when Louisa kept bugging Bambi by going over uninvited, hoping to force herself into a friendship. Frank had sat his wife down and explained to her that Bambi Arrollson wasn’t going to be her best friend. He didn’t need to tell Louisa why; everybody in Grenville knew that summer people and townies don’t mix. Like fish and fowl, they might occupy the same habitat now and again, but both had their separate spaces.

Sitting in a canoe, he and Karl could spend hours together. They were equals only when they fished.

“When do you close for the season?” Karl asked him.

“After Columbus Day. If October’s warm, I might keep a couple of units open in case we get a few more fishermen. But after that, it’s dead.”

Frank cast his line farther out, where shadows and sun dappled the water. Overhead, yellow-gold tinted leaves on the uppermost part of a maple caught the sun—one branch, sticking out of the foliage, isolated as a cowlick. No frosts at night to bring out that color, Frank knew, but enough temperature swings to start the change.

“Had a chance to sell Pine Breezes, about fifteen years ago,” Frank said, just to make conversation.

“Oh?” Karl reeled in his line, readying to recast.

“Guy wanted to put an RV park and a tent campground there. Price was okay, but what was I going to do—find another business to run? I already had the motel.”

“Sounds like you made a good decision.” Karl’s line quivered.

“You got something,” Frank lowered his voice. Both men waited. Karl’s line slackened. He reeled it in.

“Let’s try another spot,” Frank said. “These bass are gonna make us work for it.”

Frank’s arm felt strange as he started to paddle, a shooting pain as if something inside exploded. Sweat drenched his face, and he sagged forward. The paddle went into the water.

“Frank!”

Karl’s voice echoed from the other end of a tunnel.

No bars on his cell phone, but Karl tried to call 9-1-1 anyway. No service. He paddled the canoe, willing himself not to panic. If that canoe tipped, Frank would die. Closer to shore, he plunged into knee-deep water among the cattails and pushed the canoe aground. He checked the phone again; still no service.

He stretched Frank out in the canoe and put a floatable cushion under his head. He didn’t know CPR but tried three puffs of mouth-to-mouth like he’d seen in the movies. “I’m going to get help!” he yelled and began running up the path. At the parking area, two bars appeared on his phone. Karl called 9-1-1 and got instructions on what to do before heading back to the canoe where the phone disconnected from the rest of the world.

Karl sat with Frank who was barely conscious, but still breathing. That meant CPR wasn’t necessary, the 9-1-1 operator had told him. “Stay with me, buddy,” Karl said, which is what they said in the movies. He was useless; but as long as Frank’s eyes fluttered, there was hope.

“I, uh, have a brother, Curtis,” Karl began. Talking to Frank would help calm them both. “He taught me to fish when we were kids.”

Curtis used to say fishing was the only thing to do up here. While that was true, Curtis was a born fisherman, at home along any river or pond. “Went marlin fishing with him a couple of years ago, off Hawaii. He caught one about the size of a Volkswagen,” Karl said.

He checked; Frank was still breathing.

Three weeks later, on a late September day, Frank sat in a lounger, turned away from the television set and facing the sliding doors to the back deck of his house. He could hear Louisa outside talking to motel guests; maybe they were checking in, or leaving, or asking directions. He didn’t know. Louisa took care of everything at Pine Breezes these days.

His memories of his heart attack were like bookends. One side was canoeing with Karl Arrollson across Little Moose Pond to fish and on the other was waking up at Adirondack Medical Center in Saranac Lake with stents in his arteries. In between were fragments: Karl getting the canoe to shore, Karl talking to him, the state troopers and the paramedics arriving at the scene.

“We got that ticker running again—let’s keep it in good shape,” the doctor had joked with him, as if his heart were a ’57 Chevy. Frank suspected the doctor used that line with most of the patients—the men anyway. But he didn’t want to think of himself as some piece of machinery: faulty parts out, new hardware in. As much as he was supposed to be grateful—and he was, if he thought about it—he couldn’t help feeling betrayed. He’d gone out that morning with no aches or pains, no shortness of breath. He’d hauled that canoe from the back of the pickup to the water, with little help from Karl who was fifteen years older than and not exactly Mister Universe when it came to strength. Then—wham!—his heart nearly gave out. Plaque buildup had narrowed his arteries, the doctor explained. It was genetic; his father had died of a heart disease before he was sixty.

Well, if that was the case he might as well sit in this damn lounger and let the world pass him by, because there was nothing he could do to stop time or aging or death itself. His number hadn’t come up yet, but it felt damn close.

Louisa carried a tray into the room. “A little snack?”

Coffee, decaf no doubt, and two small round wafers that passed for cookies these days. “You know I don’t drink it black,” he grumbled.

“I have a little skim milk in the pitcher.” Louisa poured, and the contents of his mug changed from inky black to muddy brown. “Maybe we’ll try a few steps today. It’s a nice outside.”

“Yeah, yeah,” Frank said.

“The doctor said you should move around more.”

“I know—I was there.” Seeing the hurt on Louisa’s face, Frank regretted what he said, but he wasn’t about to take it back. Sometimes she treated him like he was incapable of hearing the doctor or reading the material from the hospital or understanding the instructions. “Maybe later.” He sipped the coffee, hot but tasteless.

The next day it rained, but that didn’t stop Louisa from suggesting they walk for fifteen minutes up and down the living room. “Like this, see?” She crossed the rug from the television to the bookshelves and back again—a whole twelve feet in each direction.

Frank gripped the arms of the chair to boost himself to his feet, then walked out of the room so Louisa wouldn’t see the tears in his eyes. In one week, he’d become an old man.

Jimmy Rivers stopped by to see Frank on his mail route. Without the summer people now, there were fewer deliveries, so he could have coffee for twenty minutes here or shoot the breeze for a half hour there. When he’d seen Louisa the other day and asked about Frank, he’d seen the worry in her face. “He just sits there, like he’s waiting to die,” Louisa had told him.

Now, he approached the back door of the house beside the motel, making good on his promise to Louisa to stop by and see Frank. He should have come sooner, but it frightened him a little to see a friend his age suddenly so debilitated. “Where’s the man?” he announced.

Louisa smiled as she let him in, but a frown still creased her forehead. “Living room,” she said. “You want coffee?”

In the living room, Frank sat in a lounger, the footrest elevated. He looked ten years older than the last time Jimmy saw him. “Stopped by Esther’s today,” Jimmy said, angling himself sideways in an armchair so he could talk to Frank. “She swears she saw Oliver—remember that snowy owl that spent the better part of March in her backyard? Wouldn’t that be something if it came back!”

Frank grunted.

“And remember that Fish & Wildlife guy who came to study the owl—Evan? Got an email from him. He’s in Guatemala with his girlfriend. That was pretty nice to hear from him.”

Frank said nothing.

Jimmy looked around the room, tiny and plain. Louisa and Frank lived in a modest, one-story house. All the upkeep and modernization went to the motel. “So when can you go back fishing?”

Frank didn’t reply right away. “I don’t know if I’ll ever do that. If I do, though, it won’t be out in the woods.”

“Plenty of places to fish by the shore.”

“Maybe I’ll get a barrel and stock it with fish,” Frank said. “That’s about my speed these days.”

Jimmy paused, wet his lips. “Hey, I have to run to Saranac tomorrow. You want to come?”

Louisa appeared out of some corner. “That’s a great idea, don’t you think, Frank?” she commented.

“She says I’m going,” Frank said. “So I guess I am.”

The next day, Frank walked slowly to the car on his own power, Louisa two steps behind him. Jimmy wanted to tell her to give Frank some space, that the more she hovered the more he probably felt like an invalid. But who was he to say anything? If he had a heart attack, Glynda would no doubt do the same.

By the time they hit the road, Frank seemed in better spirits. Saranac Lake was a bigger town, livelier with more businesses and tourists. They stopped in a coffeeshop and paid five dollars each for coffee with foamy milk and a shake of cinnamon on top. “They must have seen us coming,” Frank said.

Mannequins in store windows wore skiwear, down vests, and colorful knit hats. Child-size dummies in quilted snowsuits sat on a sled. “Rushing the season, aren’t they?” Jimmy commented.

“At least they don’t have Christmas decorations up,” Frank said.

“Gotta wait until Halloween for that,” Jimmy said, and led the way to the bookstore to see if he could find something Glynda would like.

Frank seemed tired, so they headed back. Jimmy tried to make small talk, but Frank clammed up.

“You mind me saying something?” Jimmy asked. Frank raised an eyebrow in his direction. “You can’t sit around waiting for your heart to act up or something else to go wrong. You do, you’ll shorten your life.”

Frank said nothing.

Jimmy spotted a tourist area up ahead, the kind the state marked with a big sign: “scenic view” as if people needed instructions to see something interesting. Jimmy got out of the car without looking back. Frank could stay where he was or he could come—his choice.

At the railing, Jimmy surveyed the outcropping, chiseled by wind and water. A trickle of water spouted from the rock, like some kind of miracle. He heard the car door open and shut behind him.

“People tell me all the time how lucky I am.” Frank said. “Hospital chaplain said God must have some work for me to do. And all I can think of is God’s got the wrong guy. I fish and run a motel. Ain’t nothing special about me to keep me on the planet one day more or less. Don’t get me wrong: I’m glad I still got a pulse. But it seems I’ve wasted most of it for fifty-two years.”

“Welcome to your mortality,” Jimmy said quietly. “Yours, mine, and everybody else’s. We think we got all the time in the world, then we get a wakeup call. Me? It was when I became a grandfather—made me feel like an endangered species.”

For the first time all afternoon, Frank laughed.

“Maybe the work you have to do is fishing and running that motel,” Jimmy said. “You know, if you didn’t run Pine Breezes where would people go who didn’t have a lot of money? You and Louisa give them a clean, safe place to bring their families. And Karl Arrollson? That guy wouldn’t fish if it weren’t for you.”

Frank made a face. “Let’s not go overboard, Jimmy. Karl hires me as a guide.”

“I doubt Karl needs a guide to take him to places marked clearly on a map,” Jimmy said. “He ever mention Curtis Arrollson?”

“His brother,” Frank said. “I think the two of them used to fish around here when they were young.”

There were certain lines a postal carrier couldn’t cross, like gossiping about somebody’s mail. Open it, and you could go to jail. “I’m going to tell you something you can never repeat—if you do, I could lose my job,” Jimmy said. “I delivered an envelope to Karl Arrollson about a month ago, marked ‘returned to sender.’ That envelope was addressed to Curtis Arrollson. Seems he doesn’t know where his brother is. Maybe that’s why he likes to fish with you.”

The silence between them was broken only by the splash of the water against the rock.

“Fish and fowl,” Frank said. “Guess we aren’t so different after all.”

The comment made no sense to Jimmy; then again, he doubted it was addressed to him.

Trees burst into color, drawing the last of the tourists into Grenville. Frank had to reopen three more units to keep up with the demand from travelers who found them after Louisa listed Pine Breezes on Expedia and a few other websites. They were even getting inquiries about the ski season, and now Frank planned to winterize a few units and install electric space heaters.

One afternoon, while Frank directed workmen blowing additional insulation into the walls of two units, Louisa came to get him with the cordless phone from the office. Frank sat on the bench outside. October chilled the air, but the sun felt good on his face. Karl Arrollson was on the line. They talked a bit, mostly about Frank’s continued recovery and his assurance from the doctor that he could resume all normal activity. “Which means fishing,” Frank joked. “You ever go up to the West Branch of the Ausable? They’ve got trout there and landlocked salmon.”

“That sounds great,” Karl said.

“You get a party together and let me know some dates in the spring. We’ll do it up right—three or four days. We’ll look into some cabins up that way, which is a little easier on us old guys than a tent.”

Karl laughed. “You make me wish it was spring already.”

They promised to be in touch with more details. Heading in the other direction toward the house, Frank spied Louisa in the kitchen before she saw him, smiling to herself. He slipped his arm around her waist.

“Karl and me are planning a big fishing trip in the spring,” he said. “Ausable River, up in the high peaks.”

“Not just the two of you, right?” Louisa wiped her hands on a paper towel.

“I’ll get some kids for porters, help us with the gear. Maybe I’ll ask my cardiologist to come too.” Frank nudged her. “I’m kidding on that one.”

Louisa rested her head against his chest. He pressed his lips into her hair, which always smelled lemony from her shampoo. Reluctantly, he let her go. “Got work to do,” Frank said. “Life is about to get busy around here.”

“Told you so,” Louisa yelled after him with a chuckle

Frank paused just outside the door, listening to his wife’s voice. He thought of the pair of loons on Little Moose Pond, one calling to the other. I’m here, where are you? I’m here, all is well.

Heading off toward the motel, Frank wondered once again if it was a fool’s errand to keep Pine Breezes open all year—an awful lot of extra work, which might not pay off. Then again, he told himself, maybe he’d reached the time in his life when crazy made the most sense.

More to come!

Visit us next month to read another installment in the Grenville series.Patricia Crisafulli, M.F.A., is an award-winning writer, published author, and founder of FaithHopeandFiction.com. Tricia received her Master’s in Fine Arts (MFA) from Northwestern University, which also honored her with the Distinguished Thesis Award in Creative Writing. She is the recipient of three Write Well Awards for best-of-the-web literary fiction for stories that have appeared on FaithHopeandFiction. She is the author of several nonfiction books and a collection of short stories and essays, Inspired Every Day, published by Hallmark.

Image Credit: Copyright Robert Koutny.