From Out of the Storm

Patricia Crisafulli

Original Online Fiction

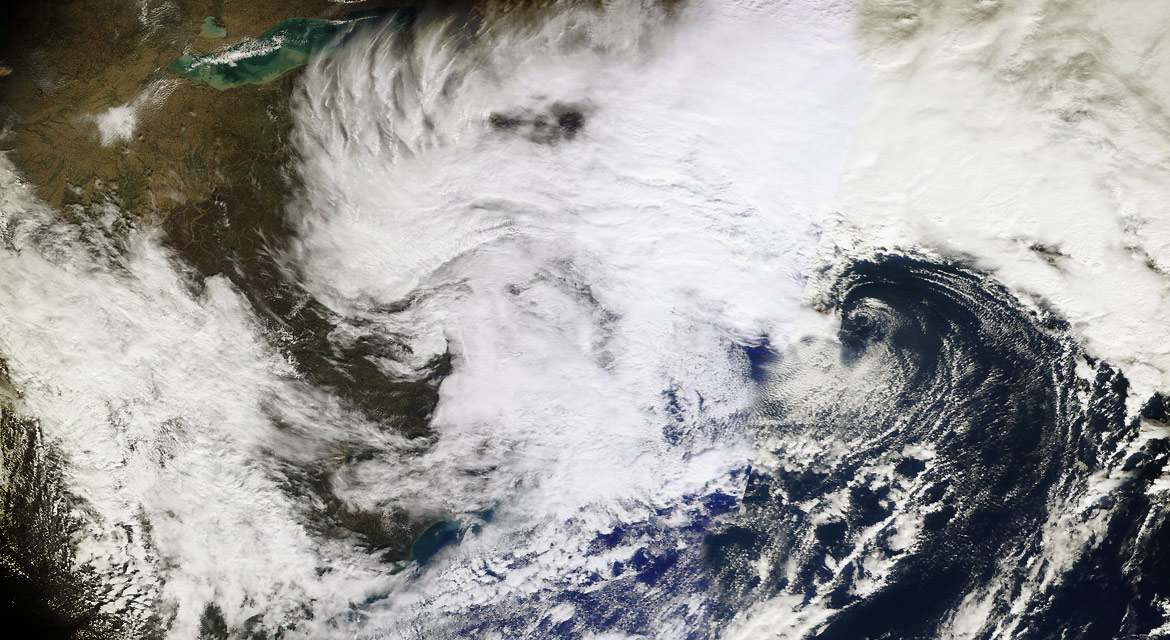

Nearly as big as a tugboat, the rig took the oncoming wave, slamming it broadside. Auggie gripped the wheel to keep both machinery and outrigging on an even keel, and shifted his weight on the brown Naugahyde seat that was split in two places to reveal the yellow foam inside. Out here, alone with his thoughts and imagination, Auggie commanded his own vessel, as if heading out into open water. Usually, he pictured the stormy Atlantic, recalled from a trip taken with his uncle when Auggie was a teenager. Back then, he’d stood at Plymouth Harbor, overcome with awe for the angry power of the gray and churning ocean. Even now, among the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains, as landlocked as a man could be, Auggie never lost the call of the once-glimpsed sea.

On many a night, out of boredom and the biting hunger of loneliness, he turned the roads into sea lanes and conjured up make-believe adventures. Sometimes he rode low in the water with a hold full of sturgeon; other times, he piloted a rescue mission to aid a capsized sailboat, a man overboard. Always, he was the captain, steady and true.

If he were younger and had to do it over again, he would have joined the Coast Guard or the Merchant Marine—gone to sea, to see the world. But other than standing on the edge of Plymouth Harbor half his life ago, his only nautical experience was riding in George Halwarth’s dingy when they went fishing on Butterfly Pond. Too late for a change now, he told himself, after being on these roads for eighteen years. Back when he graduated from high school in 1959, he rode shotgun with the older guys on the crew as they patched and paved in good weather and plowed in the winter.

Now, in this the winter season of 1976-77, Auggie drove the biggest truck in the fleet, with a double wing that could clear ten feet across. He preferred riding alone, although sometimes he got assigned some kid from the county youth program, almost always underdressed in jeans and sneakers. When the wipers got clogged and the windshield reduced to a frosted peephole, Auggie would be the one to thaw the ice with his fleshy bare hand while the kid stayed inside the warm cab with the heater and a bag of sugared doughnuts.

Out here, along the outermost county roads, the wind never stopped blowing, even in fair weather. It was still December, and the banks were already up to the knees of the telephone poles, as Auggie thought of it. By March, in some places only the head and shoulders would be sticking out of towering cliffs of snow. Houses and farms along these roads were spaced widely apart, sometimes as much as a mile with not a porchlight visible. Then somebody’s kitchen window would loom out of the darkness, grow large on approach and recede to a flicker. It must be brutally lonely, Auggie thought. If it weren’t for the county plows to keep the roads open, the people there would completely isolated.

Auggie was on his second shift of the day, having plowed all afternoon in town. At six o’clock in the evening he headed out again; if it kept snowing like this, he’d be at it until one in the morning. It was a good bit of overtime at double pay, since it was hard to find guys to work the night before Christmas. Those with families begged time off, blaming their wives, even though they didn’t fool anybody with their complaints about needing to be home with the kids and grandkids. Auggie had neither, though not for lack of desire; but he had never been the smooth one, the guy with the line and the looks. His one concession to the season would be to see his sister, Jen, and her kids the next day. He’d stop by for Christmas turkey and put the toys together, something Jen’s bum of an ex-husband wasn’t around to do even if he knew one end of a screwdriver from the other.

Turning on the radio, Auggie adjusted for the wavering signal until it came in clear with Bing Crosby singing Silent Night. Then Auggie became a sailor on the deck of a frigate, standing watch on Christmas Eve and singing carols softly to himself.

“Son of a—”

Auggie pulled hard on the wheel and raised one of the plow blades, trying not to clip whatever made the snowbank bulge out like that. Sure that it was too late, he braced for the sound of impact, for the jolt of hitting whatever was parked on the side of the road. But there was nothing other than the whine of the engine and the hydraulics. Whatever it was, he’d missed it. Or, maybe it was only snow shapes and shadows teasing him. To be certain, he stopped and backed up.

The lump in the snow opened, and a woman got out.

Panic slicked the back of Auggie’s neck over what could have happened if the plow smashed into that car. Even worse would have been flinging enough hard-packed snow to bury that car and then to have kept going without ever knowing it.

In the red glare of the brake lights, he saw her hair whipped by the wind, short boots that barely covered her ankles, and a coat that ended at her knee. Auggie got out of the cab, feeling the blast of cold through the gap of his open jacket and the untucked flannel shirt that swelled over rounded torso. “You okay?” His words were gravel in his throat.

“Yeah,” she answered in a voice as thin as a shiver.

“Anybody else in there?” Auggie feared a baby on the back seat or an elderly parent wrapped in a blanket. The relief he felt when the woman shook her head sent his breath out in a great huff. “You break down?” he asked.

“I – yeah, I got stuck.”

Auggie gauged the snow piled around and on top of the car, calculating she must have sat there for a couple of hours. He waited for the woman to say something, thinking of his sister, Jen, and her usual stream of too much information—of who and where and when and how. But this woman only stamped a little loose snow from her feet. She had to be freezing.

Auggie got into the car, but the engine wouldn’t turn over. “I could pull you out, but that won’t do no good if the car won’t start. You’re gonna need a tow truck and jumper cables.”

Again silence, which made Auggie worry that maybe there was something wrong with the woman, physically or mentally. But she was as tall as he was, and easily stepped up and into the cab. Auggie hoisted himself back behind the wheel and got his bearings. “This here’s Meyer, about two miles in from Dunn. Route 11 is about ten miles that way.” He pointed like a compass, north to south, which gave him something to do with his hands while he talked to a woman he never saw before, who was now sitting two feet from him.

Deep shivers shook her violently. Auggie turned up the heater to a noisy blast and took off his own jacket with the waxed canvas outer fabric and a quilted flannel lining that smelled of engine grease and stale sweat. Reaching over to spread it across her lap and tuck it around her legs, he felt the thin firmness of her thighs under her coat, and a fever of embarrassment spiked in his cheeks. He wound the woolen scarf from his neck around hers, trying not to brush her face or touch her hair.

“You’ll be warm soon,” he said, his words both hope and command.

Her gloveless hands came out of her coat sleeves and pulled the jacket up higher on her lap. “Thank you,” she said.

“There’s a diner out on the state highway—a 24-hour joint. I can drop you there to call a tow truck or somebody to come get you.”

The woman said nothing.

Was she in shock, Auggie wondered, maybe from the hypothermia? But that made people sleepy, and she looked wide awake. Never in his fantasies had he put himself in the place of the rescued. The truth was he had no idea of what really to do with another human being who needed help. He thought about what his heroic self in his daydreams would say in this situation. “It’s okay,” he assured the woman. “I ain’t gonna hurt you.”

The woman turned toward him, nodding. “I know that.”

“Okay then.” Auggie turned on the wipers to clear the accumulated snow from the windshield. “Nobody’s supposed to ride except county employees, but who’s gonna argue with me? Not like I could leave you there.”

No response.

The silence agonized him, an abyss he had to fill. “My name’s Auggie.” Silence. “Auggie Olaf.” More silence.

Then he heard a word spoken so faintly, he almost missed it, and had to discern it from memory. “Dawn.”

He waited for a last name, but there was nothing more. “Where’re you headed?”

“Highway,” Dawn replied, shifting under the layers of his jacket and her coat.

“You going out of town?”

Nothing.

“Well, the highway’s actually in the other direction. So maybe you got lost. We’ll get somebody here to help you. We’ll plow our way as we go. Folks around here need to get out in the morning.”

He lowered the blades and the lifted the snow back into the air, forming perfect arcs to the left and right.

“You from around here?” Auggie asked. “I live in Cranfield—over by Super-D Lumber. Been driving these roads for pretty near twenty years.”

As he glanced at her, Auggie guessed she was somewhere in her twenties, and probably at the north end of them. Auggie couldn’t shake the instinct that she was getting away from something or someone. He imagined the angry husband, the brokenhearted boyfriend pacing the linoleum in some apartment, or the argument that would have sent her out the door and into a heavy snowfall.

“You warm enough?” Auggie felt the blow of warm air coming out of the vent in Dawn’s direction.

“Yeah, feels good.” Dawn looked over at him, and this time, in the glow of the dashboard gauges, Auggie got a good look at her face: nose a little long, eyes small and makeup smudged, her snow-dampened hair starting to curl around her forehead.

Her silence encouraged him to talk the way no conversation ever had. He told her about riding these roads alone and imagining he’s out on the water, plying the harbors and the narrows. He didn’t shut up until the plow reached Route 11, which was cleared and salted by the state highway crews.

“So the diner’s that way. But now that I think about it, I’m not sure they’ll be open on Christmas Eve. The state troopers got a station not far from here. I can take you there.”

“I’m in no hurry,” Dawn said. “Got a lot of snow to clear.”

They rode together for the next four hours, all the way back to the farthest reaches of the county. During that time, his story finished, and hers started coming out. The first tentative flurries of details were followed by a great storm of what happened that evening between Dawn and the man she’d moved here with: the promises never kept, the breakup that had been coming but solidified as Christmas neared.

When his plowing shift was over, and there were no more roads to clear, Auggie brought Dawn to a gas station along the state highway. He spoke to the owner, told him where Dawn’scar was, and promised to be back there as soon as he returned the plow to the county garage.

“Might be an hour, maybe a little longer,” Auggie said.

Dawn made no promises as she gave him back his jacket. Driving out of the parking lot, he blared the big deep foghorn of the truck in salute, like a captain heading back out to deep water.

The house is quiet, the television on mute. Auggie stirs on the sofa, his back stiff from having fallen asleep. He’s got some lumbar problems from riding that rig for so many years. He should have retired five years before he did, but what was he going to do if he didn’t work?

Auggie shifts, moves a cushion, and finds a more comfortable position. He could stay like this all afternoon, watching a Sunday football game that holds no real interest other than as background noise and a distraction. One upside of retirement is having no urgency or expectation to be somewhere, although Jen’s having open house tonight since her oldest daughter is in from Boston with her husband and baby; Auggie hasn’t seen them since last summer.

His bladder gets his attention, a mission he can’t put off any longer. Swinging his feet to the floor, Auggie feels the stiffness in his right leg and goads himself to do the stretches the physical therapist wrote down for him. Doing PT at the clinic is one thing, but lying on the living room floor to repeat the movements at home takes more motivation than he can spare. Coming out of the bathroom, he heads to the kitchen to make coffee—all the better to get him moving.

And there she is.

Dawn sits on a stool at the counter, decorating Christmas cookies with such intensity, she hasn’t made a sound.

Slipping his arm around his wife, Auggie looks over her shoulder at the rows of Santa faces, angels, snowmen, and reindeer. “Thought you were out.” He kisses her cheek.

“Didn’t want to wake you.” Dawn wipes her fingers on a paper towel and adjusts her glasses. Her small eyes, with a feline glint to them, enlarge behind the lenses.

Smelling the mint and lemon of her shampoo, seeing the flecks of powder on her face, and hearing the soft clearing of her throat—among the millions of small details logged over their many years together—Auggie returns in his mind to the first time he saw her in the road. He can still picture that mound of snow opening up, and Dawn emerging like Lazarus called out of the grave. Since then, he’s come to understand how everything in his life before that moment—every real and imagined thing—led to her.

It took her a while to tell him, but eventually Auggie learned that, after storming out of the man’s house, Dawn had driven her car into a snowbank in a fit of rage and waited to be swallowed up. Then afraid that she’d die, Dawn kept the heater on until the engine quit and the battery drained. Just as she lost hope, she heard and then felt the rumble of the snowplow, her hand already on the door handle, ready to chase down another chance at life. But he had stopped, backing up in a chorus of beeps that would forever be music in her memory.

They both know something else about that night: How in the cab of that plow, she’d put out a line of her own and pulled Auggie out of his isolation. Theirs was a mutual rescue, slow and steadily completed. They rarely talk about it anymore, preferring to concentrate instead on these, the better days.

Auggie picks up one of the cookies, a perfect circle frosted into the green of a wreath and dotted with cinnamon candies. He bites down and smiles, his mouth filling with sweetness.

Patricia Crisafulli, M.F.A., is an award-winning writer, published author, and founder of FaithHopeandFiction.com. Tricia received her Master’s in Fine Arts (MFA) from Northwestern University, which also honored her with the Distinguished Thesis Award in Creative Writing. She is the recipient of three Write Well Awards for best-of-the-web literary fiction for stories that have appeared on FaithHopeandFiction. She is the author of several nonfiction books and a collection of short stories and essays, Inspired Every Day, published by Hallmark.

Image Credit: NASA, Wikimedia.org.